Today, Translation Services 24 are fortunate to welcome a guest article written by Ashley Douglas. Ashley is an Edinburgh-based researcher, writer, and translator working in Scots, Gaelic, Danish, and German. She specialises in Scots original research, writing, translation, style guide and glossary development as well as talks & consultancy. Her areas of special interest include Scottish history and archaeology, politics, linguistics, and LGBT history.

You can follow Ashley on her on Twitter or by visiting her website here. Enjoy!

Scotland’s Linguistic Landscape - Scots and Gaelic

In a previous article, we cleared up some of the confusion around the differences between Scots and Scottish Standard English. Another aspect of Scotland’s rich linguistic landscape that causes confusion is the relationship between Scots and Gaelic.

In this article, we’ll look at the differences between the two, as well as their affinities - touching on history and politics as well as linguistics.

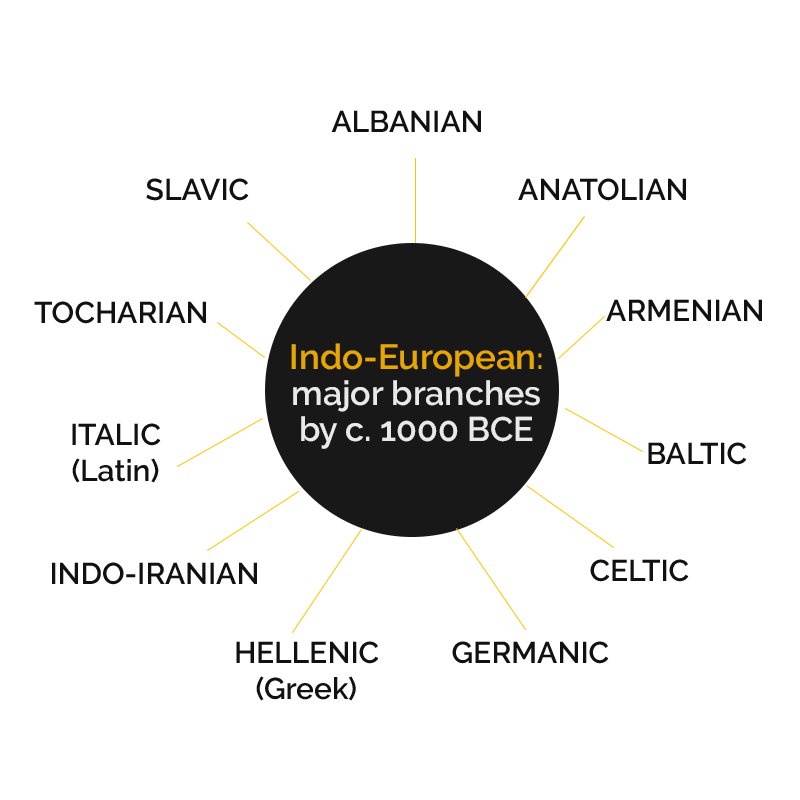

Language Family

Linguistically speaking, Scots and Gaelic belong to two entirely different language families - Germanic and Celtic respectively. These are separate branches of a postulated common ancestor language called Indo-European. By around the first millennium BCE, this had diverged into several discernible branches.

Having their respective roots in distinct linguistic branches that diverged from each other thousands of years ago, it should come as no surprise that Scots and Gaelic are, fundamentally, markedly different languages. You simply cannot mix them up. Compare the two example sentences below.

Gaelic and Scots is baith leids that is spak in Scotland

Tha an dà chuid Gàidhlig agus Albais nan cànanan a tha gam bruidhinn ann an Alba.

(Gaelic and Scots are both languages that are spoken in Scotland)

The extent of difference is immediately clear. However, to point out just a few things, the Gaelic sentence begins with the verb (as it is a verb initial language) while the Scots one starts with the subject. As to vocabulary, we can compare the words for “languages” (leids vs cànanan) or spak vs bruidhinn for “spoken”. The entire construction of each sentence, and the words used to build it, are unmistakably distinct.

Scots is a West Germanic language. It is closely related to English as well as to other West Germanic languages such as German and Dutch, and to North Germanic languages such as Danish, Swedish and Norwegian. Its roots are a northern dialect of Old English/Anglo-Saxon. It developed into a language of Scotland - in linguistic, literary, institutional and political terms - in line with Scotland’s development into a medieval nation state.

Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig) is a Q-Celtic language. It is closely related to the other modern Q-Celtic - or Goidelic or Gaelic - Celtic languages of Irish (Gaeilge) and Manx (Gaelg). Note how the terms that these languages use to refer to themselves - their endonyms - all stem from the same root. Gaelic was the language of the early medieval Scottish kingdom of Alba.

Another Celtic language group encompasses the modern P-Celtic - or Brythonic or Brittonic - languages of Welsh, Breton and Cornish. P-Celtic and Q-Celtic languages are not mutually intelligible. Although more closely related to each other than to P-Celtic languages, the modern Q-Celtic languages are not significantly mutually intelligible either.

"it should come as no surprise that Scots and Gaelic are, fundamentally, markedly different languages. You simply cannot mix them up"

Linguistic Affinities

Despite deriving from entirely different language families, there are nonetheless linguistic affinities between these two tongues of Scotland. As well as obvious instances of shared vocabulary, they often echo each other in other ways.

Let’s look at some examples.

Vocabulary

Many words have clearly travelled from Gaelic into Scots. These include now iconic Scottish words such as whisky (from uisge-beatha), glen (from gleann) and ben (from beinn) as well as loch, ceilidh, cairn, crag and sporran. All of these words come from Gaelic, and are also present in the English spoken in Scotland.

Other words have travelled in the other direction, from Scots into Gaelic. These include aidh, which is the rendering in Gaelic orthography of one of the best-kent Scots words there is: aye. This means “yes” and has Germanic etymological roots. Another example of a Germanic-derived word in Gaelic is briogais: from Scots breeks, meaning trousers.

Other words appear in both languages, but it is difficult to pin down whether they moved from Scots to Gaelic, or Gaelic to Scots; or, indeed, whether both developed independently from a common root. This group includes words such as Scots boorach and Gaelic bùrach (English: “a mess, a state”). Both of these words have, in fact, appeared in the Official Report of the Scottish Parliament, with Gaelic or Scots orthography dependent on context.

It is also worth noting the Gaelic word Sasannach, which has travelled into Scots and Scottish English but gained pejorative connotations along the way, and is often used insultingly. In Gaelic, the word has no negative baggage, but is simply an adjective or noun relating to Sasainn, the word for England.

"Many words have clearly travelled from Gaelic into Scots."

In other cases, it is less about shared vocabulary per se, but about the ease of idiomatic translation between the two languages. For example, upon learning the Gaelic saying tha mo cheann na bhrochan (“my head is porridge”), the Scots speaker will not miss a beat in translating to ma heid’s aw mince. No such immediately perfect English translation comes to mind; the English language would frame the sentiment entirely differently. Similarly, where it can be tricky to translate the Scots term shooglie into a satisfying one-word English equivalent, for the Gaelic speaker, translating it to cugallach feels natural.

Syntax

Definite Article

First of all, Scots and Gaelic exhibit markedly more widespread use of the definite article in relation to both adverbs of time and with nouns.

They are at the schuil the noo

Tha iad anns an sgoil an-dràsta

They are at [-] school [-] now

In the example above, Gaelic and Scots both define the school / an sgoil and use the definite article before the time adverb (the noo / an-drásta).

The Scots and Gaelic for “today” and “tomorrow” have a similar definitive feel, absent in English:

the morra, the day

a-màireach, an-diugh

tomorrow, today

Scots and Gaelic also use the definite article in relation to languages in a way that English does not. For example, Scots refers to speaking “the Doric” or “the Gaelic”, or to someone studying “the German”. Similarly, Gaelic refers to itself in many contexts as “the Gaelic” (a’ Ghàidhlig) and to English, for example, as “the English”; e.g. anns a’ Bheurla” = “in (the) English”.

Preposition Dropout

In another case, however, Scots and Gaelic are defined by their lack of something present in English: namely, the preposition “of”. For example, compare Gaelic “beagan uisge” and Scots “a bit watter” with English “a bit of water”.

Singular Nouns

Both Gaelic and Scots use singular nouns in certain contexts where plurals are required in English.

Gaelic: trì bliadhna

Scots: three year

English: three years

(Note: Gaelic bliadhna is the singular form of “year”. The plural form would be bliadhnaichean).

Reflexive Pronouns

Both Scots and Gaelic use the reflexive pronoun forms far more comfortably and freely than in English.

It's yersel

Thu fhèin a th’ ann

It’s you

Hoo’s yersel?

Ciamar a tha thu fhèin?

How are you?

Second Person Plural Pronoun

Both Scots and Gaelic have a second person plural pronoun; as, indeed, do the vast majority of European languages. English is very much the odd language out in not having one. Compare Gaelic thu (singular) and sibh (plural) and Scots you/ye (singular) and youse (plural) with English you (singular) and you (plural), which are identical.

Phonology

The phonemic inventories (the sounds) of Scots and Gaelic coincidentally share the fricative “ch” sound so associated with the speech of Scotland, including the English spoken in Scotland. This means that this sound is easily produced by speakers of Scots, Gaelic and Scottish English, whereas English speakers elsewhere are unlikely to have the [x] sound in their inventory.

This applies to the [x] sound produced after what are known as broad or back vowels (such as in loch) as well as the [ç] sound (an allophone) produced after slender or front vowels (such as in dreich).

If you can competently pronounce those sounds and you read out those words, you will hear a subtle difference in the quality of the “ch” sound depending on the type of vowel before it: this is because [x] is a voiceless velar fricative while [ç] is a voiceless palatal fricative.

Gaelic speakers do not struggle at all to pronounce Scots words such as dreich, trauchle, thocht, broch, brocht and eicht, and Scots speakers do not struggle at all to pronounce the “ch” sound present in countless Gaelic words, from loch and smaoineachadh to ach and deich .

The place known in English as Burghead is known in Scots as Burgheid or, more commonly, The Broch. In Gaelic, the placename is Am Broch. It is easy for a Scots or Gaelic speaker to flit between The Broch and Am Broch, depending which tongue of Scotland they are speaking. It is less easy for a speaker of English who has not mastered the “ch” sound to comfortably use either the Scots or the Gaelic term.

(Note that another Scottish town, Fraserburgh, is also known locally as The Broch).

Reflection

Clearly, Scots and Gaelic are fundamentally very different languages. However, the existence of a range of affinities in syntax, phonology and sentiment, as well as vocabulary, is evident.

Even allowing for some aspects to have arisen independently and from different roots - for coincidence rather influence in the first instance - their presence in both Scots and Gaelic conceivably affirms them in each other in a mutually reinforcing and mirroring manner.

Meanwhile, other aspects seem likely to reflect, to varying degrees, the centuries of co-existence of Scots and Gaelic speakers in Scotland and the mutual influence they have had on each other’s languages and world views.

Certainly, for the Scots speaker learning Gaelic or the Gaelic speaker learning Scots, there are far worse places to start from.

This is an under-researched area of Scotland’s linguistic landscape. More study is needed both synchronically (into what Scots and Gaelic are like today) and diachronically (into how they came to be that way and what they were like historically).

In addition, specific dialects of Scots will exhibit more and different affinities with Gaelic, depending on their particular historical development and geography. The author looks forward to more research, learning and discussion on all of the above.

Terminology

Many centuries ago, the Gaelic spoken in Scotland was referred to as lingua Scotica, lingua Scotorum and Scottis. That is, it was called the language of the Scoti or Scots, based on the term used by the Romans to describe early Gaelic-speaking peoples - or Gaels.

Jumping forward a few centuries, by the 1500s, this language of “the Scots” had come to be referred to as Ersch, Ersche, Eirse or Erse, all of which are historical Scots language terms for “Irish”. This reflected the traditional view that Gaelic was brought to Scotland from Ireland, although this narrative is challenged by archaeologists and historians today.

Neither of these terms are now used to describe the Gaelic spoken in Scotland. In Scottish English and Scots, it is called Scottish Gaelic, Gaelic or the Gaelic - these are its exonyms. In Gaelic itself, it is called Gàidhlig - this is its endonym.

Crucially, please note the preferred pronunciation of Gaelic and Gàidhlig as GAH-lik [/ˈɡælɪk/] in Scotland and not GAY-lik [/ˈɡeɪlɪk/], which refers to the Gaelic spoken in Ireland.

Meanwhile, until around the 15th century, Scots was most commonly referred to as Inglis. That is, it was referred to as “English” or the “speech of the Angles”. This tribe arrived in south-east Scotland around 600 AD, bringing with them the Germanic sounds and words that would eventually develop into the Scots language in Scotland.

In the medieval period, however, Scots speakers began to refer to their language as Scottis instead of Inglis. This transition took place in line with a strengthening sense of Scottish national identity in a medieval Scotland in which Scots was the dominant language. As noted above, at the same time as Scottis came to apply to Germanic Scots, it ceased to apply to Celtic Gaelic, which began to be referred with exclusionary and othering Scots words meaning “Irish”.

The modern term Scots developed from the medieval Scots term Scottis.

Today, Scots is referred to in English as Scots, Lowland Scots or Broad Scots. In Scots itself, it is often called the Scots leid. Lallans is another Scots endonym to refer to Scots, although it is more literary, as is Braid Scots.

You will also frequently hear reference to distinct dialects of the Scots language, from Doric and Glaswegian to Dundonian and Orcadian. Note that, historically, the term Doric referred to Scots as a whole, but has now narrowed in meaning to refer only to north-east Scots.

In Gaelic, Scots is referred to as Albais [/aLabɪʃ/].

Note that it was previously termed A’ Bheurla Ghallta; literally, “the English of the Lowlands”, whereby Gallta (“Lowlands”) has a secondary meaning of “alien/foreign”. This term is problematic and is not embraced by Scots speakers.

Remembering that Scots = Germanic and Gaelic = Celtic may be a useful way to make sure you’re using the right terminology and thinking about the right language of Scotland today.

Geography and History

In recent centuries, Gaelic’s heartlands have been the western Highlands and west-coast islands of Scotland. However, it is not confined to those areas and is spoken across Scotland today. There are strong communities of Gaelic speakers outwith those rural heartlands, including in urban settings, and centred not least around Gaelic-medium schools in cities such as Edinburgh, Glasgow, Aberdeen and Inverness. The number of speakers of Gaelic today is pretty evenly split between Highland and Lowland Scotland.

In the 2011 Scottish census, 87,100 people aged 3 and over in Scotland - 1.7 per cent of the population - reported that they had some Gaelic language skills.

Historically, too, Gaelic has been present far beyond the west-coast islands and western Highlands. Gaelic was the language of the earliest Scottish kingdom and court; the kingdom of Alba.

The legacy of this early medieval era of Gaelic dominance and prestige can be seen in particular in the preponderance of Gaelic place names and landscape terms all across the map of Scotland today. Although exact derivations are often hard to pin down, countless Scottish place names have Gaelic origins. For example, Craigentinnie, near Edinburgh, most likely derives from Creag an t-Sionnaich, ‘the fox’s rock’, while Invervurie comes from Inbhir Uraidh, which is Gaelic for ‘mouth of the river Urie’. In between those two places, Auchtermuchty in Fife derives from the Gaelic words uachdar (upper), muc (pig) and garadh (enclosure).

Gaelic’s widespread influence in Scotland is also of course reflected in the numerous words of Gaelic origin that still characterise Scots and Scottish English today.

However, as touched on above, Gaelic came to be displaced as the dominant language of the realm by Scots, the Germanic tongue first brought to south-east Scotland by the Angles. This Scots takeover was connected with the significance of the burghs and the dominance of Scots in their operation.

From around the 1300s, Scots had established itself as the prestige language of the kingdom. It was now the language of kings and queens, poets and parliamentarians, law and high literature - as well as the spoken tongue of countless thousands of ordinary people across the land, who have left us no written records. Scots held this position until around the 1700s, when it, in turn, was displaced by English as the formal language of the Scottish state.

However, just as Gaelic did not disappear from Scotland after being displaced as the formal language of the kingdom many centuries ago, neither has Scots ever ceased to be spoken and written in Scotland.

In the 2011 Scottish census, 1.5 million people reported that they could speak Scots, and 1.9 million reported that they could speak, read, write or understand Scots - which is nearly one third of Scotland’s 5.2 million population.

Scots is spoken across the country today, from the southernmost parts of the Scottish Borders, neighbouring England, to the tip of the northernmost part of the Shetland Isles, neighbouring Norway. It is spoken in urban centres such as Edinburgh and Dundee and in more rural areas such as the north-east and the Northern Isles. It is poorly represented only in the western Highlands and west-coast islands, reflecting where Gaelic has been more significantly present in recent centuries.

Although minoritised today, both Scots and Gaelic have previously been the cause of the demise of another language. Pictish disappears when Gaelic takes over as the language of early medieval Scotland. Later, the Scots-speaking state of the later medieval period oppresses and others Gaelic. After that, Scots is sidelined in favour of English, and the existing displacement of Gaelic is entrenched. We should avoid falling into the trap of thinking that any language is inevitably or perpetually victim or oppressor. Just as all peoples can be oppressed or oppressors, so can languages - as they are spoken by people.

Conclusion

Scots is a Germanic language. Gaelic is a Celtic language. However, despite this fundamental difference, they exhibit aspects of linguistic kinship as well as shared vocabulary.

Linguistics aside, both have been the dominant language of Scotland at different points in its history, and both are still spoken and written across Scotland today. Both lay claim to works that rank among the greatest of Scotland’s literary output. Both are worthy of respect. Both are unique and precious. And both need protection, preservation, and promotion today.

Translating content into high-quality and idiomatic Scots and Gaelic, thereby making visible and validating those languages and their speakers, is a core part of that. There are top-class Scots and Gaelic translators ready and willing to help you translate any of your material into these languages of Scotland, supporting you to target specific new audiences and to contribute towards preserving minoritised languages at one and the same time.

TranslationServices24 Ltd. | LR UK Group

Registered in England & Wales with Company Number: 07635166. VAT Number 154 4490 09

2022 - All rights reserved